Jacob and the Corpse Candle

It was early.

The sun was barely over the horizon, and the sky over St. Lawrence looked ominously pink.

Tom McGrath looked from his kitchen window. Beyond the churchyard, he could see a dark smudge of cloud forming on the horizon.

Tom shook his head and lit the stove. It wasn’t going to be a good day.

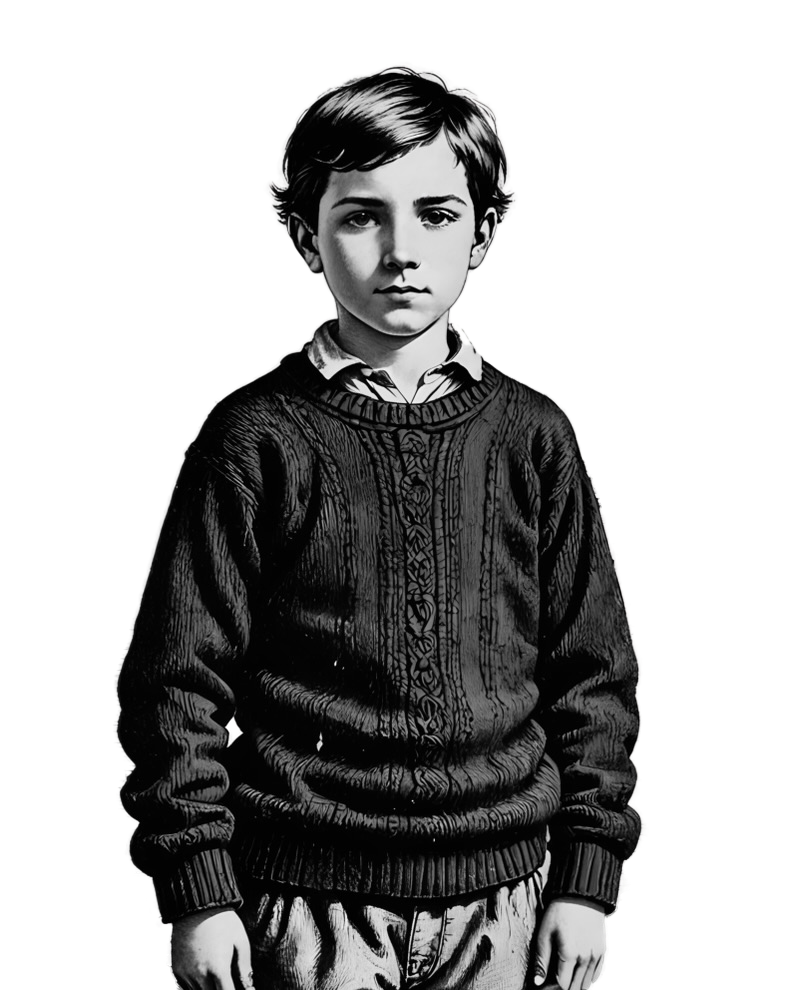

Upstairs, his twelve-year-old son Jacob slept.

The boy was getting older, almost—but not quite—a young man. Once upon a time, he’d have been downstairs as soon as he heard Tom stirring, but these days he clung to the bed a little longer.

“Everything changes,” Tom sighed to himself.

There had been too much change in the tiny saltbox already. Barely a year had passed since Tom’s father had died. For a long time, it had been three generations of McGrath men—grandfather, father, and son—under one roof, living and working together.

Now, his father was gone, buried in the churchyard just down the path. Through the window, Tom’s eyes followed a slow line from the church cross to the cemetery below. He could just make out the old man’s grave.

This last year had been hard.

Jacob had helped where he could, but he couldn’t do the work of a grown man—and besides, there was school. Tom needed the boy to get an education. So he picked up the slack, doing the work of two men as best he could. And it wasn’t just that. His father had been a rock in his life—a steadfast guide. He’d helped him through so much: the death of his mother, and later, his young bride.

Life had always been hard, but life without him felt immeasurably worse.

Tom slowly exhaled and closed his eyes. He’d get through it somehow, he supposed. Perhaps he could—

But before he could finish his thought, a sound caught his attention. There was motion upstairs.

The boards were creaking as someone moved slowly from one room to another.

What could Jacob be doing? he thought.

He called out, but there was no reply.

Tom went upstairs.

It was always shadowy on the second floor of the old house. He should have taken a lamp; in these early hours, there was barely enough light to see.

He peeked into Jacob’s room. The quilts were twisted and pushed to the foot of the bed, but the boy was still asleep. His breaths were slow and regular.

Behind him, the floor creaked again. The sound was coming from inside his father’s old room.

Tom froze. The room had been shut up for almost a year now; after his father died, he hadn’t wanted to face the emptiness.

But now, someone—or something—was moving around inside.

Tom reached for the doorknob. His heart quickened. He had to look inside, but everything in him told him to turn away—that he did not want to see what lay beyond that door.

He swallowed hard and turned the knob.

A rush of cold, stale air swept past him as he stepped over the threshold.

If something had been moving around, there was no sign of it now. Things were just as he remembered.

Even now, a year later, the smell of his father’s pipe smoke seemed to linger in the air. Tom closed his eyes and breathed it in. For a moment, the last year seemed to fade away—the grief, the worry, and the pain were gone, swallowed by a beautiful golden glow.

He opened his eyes, and the shadows returned.

Closing the door, he returned to the hallway. He was sure he’d heard movement—he’d have staked his life on it.

As if on cue, the noise started again, this time from the staircase. One creak, then another, slow and deliberate, like the weight of a man descending.

“Jacob?” Tom called, though he already knew it wasn’t the boy. The steps were heavier. Older.

He rushed to the banister—and froze.

There was no one on the stairs.

Instead, hovering halfway down, was a small flickering flame.

It looked, for all the world, as though a candle were burning in midair—except there was no candle, no wax, no wick. Only a golden flame, steady and sure, moving slowly toward the bottom of the stairs.

Tom flew after it, following it through the kitchen to the porch, where it passed through the closed door.

From the window, he watched the light drift down the path toward the cemetery, through the gate, until it faded in the early morning light.

He’d never seen anything like it.

Tom returned to the kitchen. He felt cold. He paced back and forth in front of the stove, his heart racing.

He had to do something normal. He reached for his pipe, packed the tobacco, and struck a match—but the flame trembled in his hand. He let it die and set the pipe aside.

The events of the morning left him unsettled. He rubbed his temples. He didn’t know what to make of it—any of it.

By the time Jacob came downstairs, the kitchen was bathed in sun. The boy squinted, raised a hand to his eyes, and fell into a kitchen chair, his back to the window.

“It’s too bright,” he muttered.

Tom glanced toward the window. The sun was soft, no harsher than any other morning.

He poured two cups of tea, picked up a crusty heel of bread, broke it, and set half before the boy.

He thought about telling Jacob about the light—asking if he’d seen or heard anything unusual in the night.

He turned the words on his tongue, trying to find the right way to broach it.

“Did you…” He stopped.

The boy was carefully pouring the tea from his cup into the saucer. He looked so young.

Suddenly, Tom didn’t want to burden him with such strange stories.

So instead, he said, “You’ll need to fill the lamps after school, and trim the wicks.”

Jacob nodded with a quick, boyish smile. He seemed happy, unencumbered by worries, untouched by the weight of adulthood.

Remember him like this, Tom thought. Time goes by too quickly.

As the boy left for school, Tom stood at the window watching him go slowly down the path—past the churchyard gate, where the light had vanished earlier that morning.

He didn’t understand the impulse, but for a moment, he nearly called after him—asked him to come back.

He let the idea pass, turning to work instead. There were nets to mend, but his hands were sluggish and his mind elsewhere. Before long, frustration set in, and he tossed them aside.

Tom wandered to the stage door and looked up at the house, at his father’s bedroom window.

A year ago, before his father died, he could have spoken of it—the footsteps, the strange light. The old man would’ve listened. But now, there was no one.

He sighed.

Then, from the corner of his eye, he caught movement—Jacob was coming slowly down the path toward the house.

He shouldn’t have been home yet; school wasn’t over.

Tom hurried to meet him.

“Teacher sent me home,” Jacob whispered. “My neck, my head…” He grimaced. “Some wonderful pain.”

Tom put his hand to the boy’s head—he was burning up.

He scooped the boy into his arms and carried him into the house—through the porch and kitchen, up the creaking stairs to the cool dark of his bedroom.

The doctor came but offered little hope. The fever would have to run its course.

By nightfall, only a single candle burned on Jacob’s dresser. The bright glow of the oil lamp was too much for his eyes.

Tom sat beside him, holding a pan of cool water, wringing cloths and placing them on his son’s little body.

The boy was lost in a delirium—drifting between his sickbed and some shadowy dream.

Tom was convinced that every rise and fall of his chest would be the last.

He remembered his father’s passing—

and the horrible realization that the end was near.

He felt it now, too.

He would never survive this.

Jacob was his boy—all he had left.

Life couldn’t—shouldn’t—go on without him.

Tom leaned forward, his head in his hands. He wanted to pray, but the words caught in his throat. Instead, he sobbed. If there was mercy in heaven, he couldn’t see it.

Lost in grief, Tom didn’t hear the floorboards creak outside, or feel the chill that slipped through the room.

Jacob’s chest lifted once, twice.

Then, slowly, his eyes opened. His gaze was clear and present—fixed first on his father, then on something just beyond his shoulder.

“It’s all right, Dad,” he whispered.

“Pop is here… he knows the way... and I’m not afraid.”

The candle on the dresser flared, bathing the room in soft golden hues—and for a moment, Tom felt the house was whole again.

Then the light dimmed, and the boy was gone.

Through the window, the first thin fingers of morning crept above the horizon.

In minutes, they would reach the churchyard—the place he would now bury his son, beside his father, the man who had come back to light the way.

With the soft flicker of a flame,

the dead had come for the dying, and

a grandfather had led his grandson home.

Tom looked toward the dresser, at the candle, and felt it—

the kind of love that, even after death, would never let go.

Corpse Candles

This story is inspired by a corpse candle sighting in St. Lawrence recorded in P.J. Kinsella’s 1919 book Some Superstitions and Traditions of Newfoundland. Kinsella learned of the event from a local gentleman, who claimed the strange occurrence had happened only a short time before.

Corpse candles or corpse lights are an old European superstition that found a foothold in Newfoundland. These lights are believed to be souls of deceased relatives, appearing as flames that come from the graveyard to summon the spirit of a dying person.

The appearance of a corpse candle is often seen as a sign that someone close to the family is about to pass away. It was believed not only to foretell death, but to guide the spirit of the soon-to-be deceased to the afterlife.

-

Some Superstitions and Traditions of Newfoundland, P.J. Kinsella, 1919

Vikings of the Ice, G.A. England, 1924