Death at the Barn Dance: The K of C Fire

It was just about 11 pm.

Around St. John’s radio dials were tuned to VOCM for the Saturday Night Barn Dance live from the Knights of Columbus Hostel on Harvey Road.

Suddenly the singing stopped.

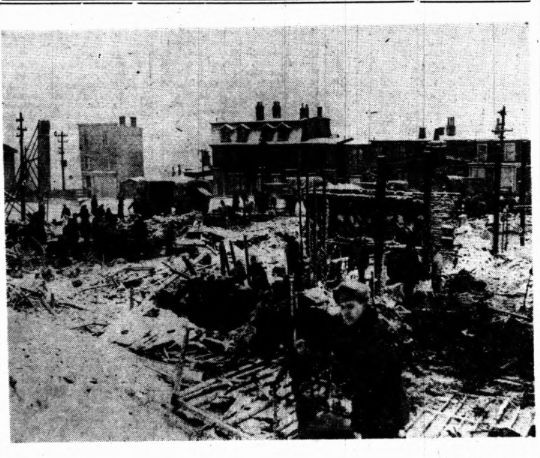

K of C Hostel, Image from The Daily News, Dec 14, 1942. MUN DAI, Creative Commons

Over the radio a commotion could be heard, then the sound of muffled explosions, followed by panicked voices screaming “Fire!”

Production cut the broadcast but, back at the station, they could still hear the pandemonium unfolding until fire destroyed the microphones at the Hostel.

In little more than an hour the K of C building was gone and with it, 99 people.

In terms of death it was the worst building fire in, not only Newfoundland, but all of (what is now) Canada.

And it may not have been an accident.

The Knights of Columbus Hostel

This all happened on December 12, 1942 when Newfoundland was at war. The Knights of Columbus Hostel was a new building. It opened in 1941 to provide service for military personnel stationed in St. John’s. It had a restaurant, dormitory, rec. room and an auditorium.

It was in this auditorium that the barn dance was held. That Saturday night somewhere between 350 and 500 crowded into the space to listen to Uncle Tim's Barn Dance Troupe — a popular act at the time.

The Fire

Just after 11pm Eddy Adams, a Canadian soldier, took to the stage.

Unbeknownst to Adams, or anyone else in the auditorium, there was a fire burning in the attic. It seems the fire had been burning awhile and consumed much of the available oxygen (a fact supported by apparent carbon monoxide poisoning in some of the survivors).

A gentleman from the Newfoundland Militia went upstairs to find a bathroom, he opened a door and came face-to-face with a wall of flames.

With a fresh supply of oxygen the fire exploded, tearing through the roof.

Back in the auditorium, Adams had just begun singing "The Moonlight Trail" when someone yelled “Fire! Fire! Fire!”

It was already too late.

“In its horror it stands unequalled by anything in our experience. And whatever the cause, unless it were sabotage or lunatic and criminal malice, human error is at the root of most of it.”

The Daily News, December 14, 1942

People pushed to the exits but struggled with the doors. In a lapse in judgement the doors swung inward to open — exactly opposite the movement of the crowd. Worse than that, according to reports, some doors were blockaded due to the wartime blackout.

Some of the crowd thought to jump through the windows but there the blackout created problems too — the windows had been screened to prevent light from escaping. Eventually, some screens were broken, but it cost them valuable time.

In little more than an hour the Knights of Columbus Hostel was gone and, along with it, 80 Canadian, British and American servicemen, and 19 civilians.

Hospitalized victims of the Knights of Columbus Hostel fire, St. John's, Newfoundland, 13 December 1942.

Credit: Lt John D. Mahoney / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-114434

Sabotage?

Remains of the K of C Hostel, Image from The Daily News, Dec 14, 1942. MUN DAI, Creative Commons

The cause of the fire has never been definitively proven but almost immediately people began to wonder whether St. John’s was home to an enemy operative, intent on inflicting damage on wartime infrastructure in the city.

Justice Brian Dunfield was tasked with investigating the disaster. He was of the opinion that the fire was, indeed, of suspicious origin — though he was unable to establish a definitive motive.

One of the factors he considered was the fact that the K of C fire was not an isolated event. In the weeks after the fire there was an unsuccessful attempt of arson at the city’s YMCA Hostel. There was another fire at the Old Colony Club, which was used by service personnel, that lead to 4 more deaths. On top of that, there was a suspicious fire extinguished at the U.S.O. club in the city.

Further afield, there was an apparent arson attempt at the K of C Hostel in Halifax.

It was getting hard to believe all this destruction could be coincidence. Whether it was the work of a homegrown arsonist or the actions of an enemy agent couldn’t be proven.

The fact that Newfoundland had been the site of much enemy action in the previous months swayed belief toward the latter.

Enemy Action in 1942

World War II really came to Newfoundland’s shores in 1942, albeit mostly on the water.

On September 4, 1942 German U-boat 513 sunk the Strathcona and Saganaga just off Bell Island killing 29 people.

Little more than a month later, on October 15 a U-boat (U-69) sank the SS Caribou (the ferry between Newfoundland and Nova Scotia) killing 136 people.

Then, in November, U-518 hit Scotia Pier in Bell Island and sank the Rose Castle and S.S.PLM 27, killing 40 people.

It had certainly been a tragic fall. By the time December rolled around, it must have been easy to believe the fire was an enemy action —

and maybe it was.

Legacy

What is not debatable is the scope of the tragedy.

99 people died in the blaze and many survivors were seriously injured. To this day, it remains the deadliest building fire on (what is now) Canadian soil.

It’s a terrible distinction, but one we can all hope it keeps.

-

The Daily News, Dec 14, 1942

The Western Star, Dec 18, 1942

The K of C Fire, 70 Years Later, Darin McGrath.

Newfoundland’s Furious Fire by Sabotage, Frank Rasky

Bell Island Sinkings, NL Heritage.

The Sinking of SS Saganaga and Lord Strathcona, Community Stories

When World War II came to Newfoundland Botwood was forever changed — and Bob Hope got to add a joke to his repertoire.